It can be argued that the Famine was the first natural disaster (albeit one capitalized upon by London) to spur international fundraising. A few examples:

It can be argued that the Famine was the first natural disaster (albeit one capitalized upon by London) to spur international fundraising. A few examples:

Irish in NYC (where they were a quarter of the population) sent home approximately $900,000 in 1847 alone and probably a bit less the year before. This amount represents private monies between families and is not part of the U.S. relief contributions which totaled in the millions.

Irish serving in the British army as well as ex-pats and natives of Calcutta, India, sent £14,000.

Abraham Lincoln (then a Congressman) donated $10.

The members of New York City’s Shearith Israel synagogue sent $1,000.

The Choctaw Indians of Oklahoma raised $170.

The city of Hackensack, New Jersey, gave 4 boxes of clothing.

The prisoners of New York’s Sing Sing prison sent relief money.

Jewish banker Lionel de Rothschild began fundraising in 1847, receiving donations from Venezuela, Australia, South Africa, Mexico, Russia and Italy. 15,000 people contributed £400,000.

Contributions came from Turkey, Mexico, Barbados, Bombay and Australia.

Irish American dock workers waived their salaries to load ships bound for Ireland.

American railroads waived fees for relief supplies.

Under pressure from English Quakers, the British Government agreed to cover freight costs of shipments from the U.S.

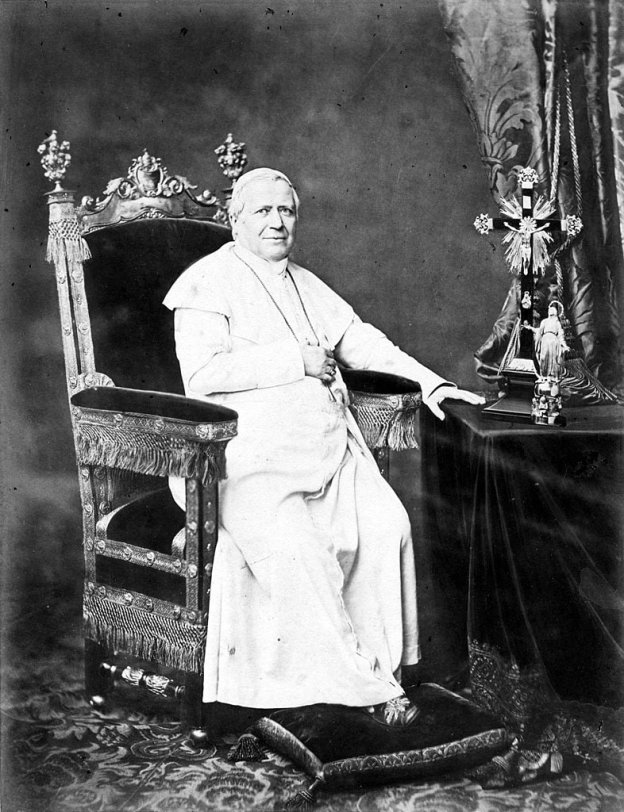

Queen Victoria gave relief money and wrote fundraising letters, but seems to have done nothing behind the scenes to affect a change in British policy. Her Famine visit to Ireland (as detailed in another post) was a financial drain on Ireland’s limited resources.

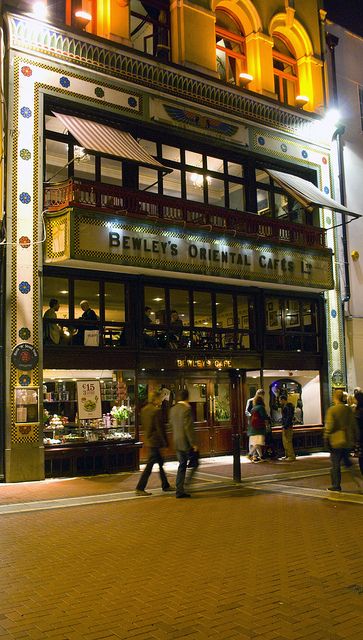

The Irish Catholic Church used its international network to raise huge sums. Donations flowed in from North America, South America, South Africa, New South Wales, France, Italy and Austria.

The Quakers kept copious notes of monies raised and dispersed. It is very emotional indeed to read the lists of U.S., Canadian and British cities that contributed food and clothing. Of course, Boston & New York are in the forefront, but here are a few others: Darien, Savannah, Portland (Maine), New Orleans, Louisville, Georgetown, Rochester, Madison, Utica, Charleston, Cincinnati, Richmond, Newark, Philadelphia, Baltimore.