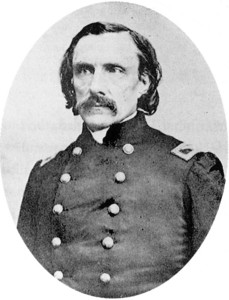

John O’Mahony, who was tasked with establishing the American-based Fenian Movement. O’Mahony derisively referred to Irish Americans as ‘tinsel patriots’ but understood the necessity of American money and influence if Ireland was to achieve independence.

John O’Mahony, who was tasked with establishing the American-based Fenian Movement. O’Mahony derisively referred to Irish Americans as ‘tinsel patriots’ but understood the necessity of American money and influence if Ireland was to achieve independence.

Although Irish had struggled, in one form or another, for independence from Britain throughout its 800-year subjugation of Ireland, it was the horror of the Famine that gave birth to the international independence movement known as the Fenian Brotherhood*. The Fenians (of which the Irish Republican Brotherhood, a precursor to the IRA of modern times, was part) had much in common with the Irish secret societies which had come before in that they advocated violence in pursuit of Irish independence, but the Fenians went one step further. Whereas previous secret societies had been agrarian-based and mostly local, the Fenians saw the struggle for Irish independence as one where diaspora Irish could not only have a voice but play a part. Brilliant, if twisted marketing: Irish Americans might not be able to fight the British directly, but they could subsidize those who did by providing cash, arms, political influence and secrecy. Think of it as a perverse take on the penitential power of the survivor: through actions taken in America, Irish Americans could help free their brethren suffering under British rule much as the actions of the living could affect the fate of loved one’s awaiting judgment in Purgatory.

American aid for the Fenians ebbed and flowed with the fortunes of working class Irish Americans during the decade following the Famine. The economic recession that gripped America in the early 1860’s might have temporarily dried up financial support, but the American Civil War provided military training for thousands of Irish Americans and legitimized the belief that resolving sectarian violence by force was justified.

The Civil War also inflamed Anglo-American relations. Although Great Britain was officially neutral during the war, its shipyards built two warships for the Confederacy and an international tribunal subsequently awarded the U.S. 15.5 million dollars for damages done by these British-made ships. Would the British more overtly aid the South? Fears ran high at times. Confederate president Jefferson Davis believed that Britain’s dependence on Southern cotton would be a decisive factor in garnering British diplomatic and military support for secession. Unfortunately, he did not factor in Britain’s long-standing tension with France and her growing distrust of Bismarck’s Germany – both of which claimed London’s attention and resources. For his part, President Lincoln endeavored to portray the War Between the States as only that: an internal conflict, not a matter within the purview of international law.

As to the issue of slavery, it had been outlawed in Britain for thirty years (G-d bless the memory of William Wilberforce and his colleagues), so to support a Southern economy so dependent on the slave trade would have been a hard sell for London at home. Then there’s the 1861 Trent affair during which a U.S. naval vessel fired on a British (neutral) ship carrying two Confederate emissaries to Europe. Although the British fleet was put on a war footing as a result and there was much saber rattling in Whitehall, Lincoln sagaciously released the captured men, confident that this conciliatory move, coupled with the fact that the North was providing Britain with 30% of its grain imports at the time, would defuse tensions. He was right – in this as in so much else. Still, for the first years of the war it appeared that the South might win or at least not lose. If that happened, would London weigh in? If so, what would France do? All of this uncertainty meant that anti-British sentiment during the War ran high – a boon to the efforts of the Fenians who made great strides at the time on the public relations front. Their efforts in the 19th Century may have failed to free Ireland, but they laid a foundation of support in America that materially sustained the Fenians and their IRA offspring during the Troubles to follow. Thus history came full circle, for it was Famine survivors who had been forced by British action and inaction to emigrate to America who were to prove such an effective weapon in the war for Irish independence.

* named for the Fianna, a mythical military unit led by the warrior Finn MacCool who protected Ireland from foreign invasion.