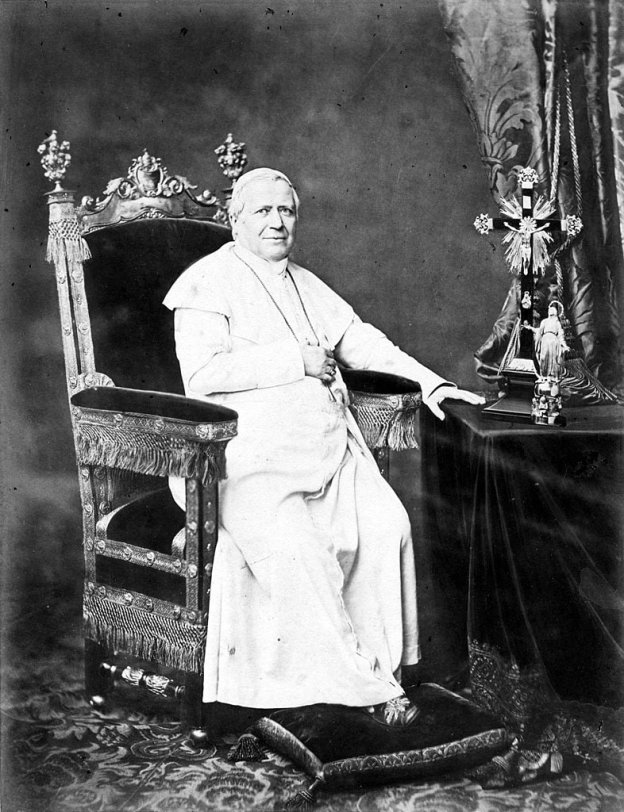

In 1846, the second year of the Famine, Pius IX was elected Pope. He assumed control of the Papal States at a time of great political and social upheaval in Italy. Initially hailed as a progressive reformer, once he’d personally experienced the chaos born of Italian nationalism and Austrian aggression, his attitudes changed dramatically.

One could argue that, when the political autonomy of the Papal States was slipping away, Pius IX wasn’t positioned to help the starving Irish aside from encouraging individual Catholics (not the establishment) to give to Irish relief (and he set a personal example by giving of his own purse) and to pray for the Famine’s victims.* One could argue that, but I won’t. The Pope was a political and spiritual leader of great influence and a young man (54) with the energy to affect change. That he chose to use that energy and influence to remake the Catholic Church in England – something that hadn’t been done since the Reformation – and secure London’s undertaking to grant him political asylum should he need to flee Italy speaks to his priorities vis-a-vis Great Britain. How much could he have accomplished if he’d chosen, instead, to use what influence he had with London to champion the cause of the starving? What if he’d used the Vatican’s considerable wealth to save lives? We’ll never know what Pius IX’s legacy would have been if he’d put the lives of Irish Catholics first, but we do know a bit about what the Irish Church accomplished.

Irish parish priests and Church leaders set up soup kitchens, raised funds and sought to exert political pressure both within Ireland and abroad. Archbishop Daniel Murray of Dublin, 77 at the start of the Famine, stands out for his efforts. A man who advocated non-denominational education, encouraged Catholics to attend Queens (Protestant) College, supported Daniel O’Connell’s emancipation movement and was instrumental in establishing Dublin’s first Catholic hospital, Murray deserves a few hundred pages of description to adequately catalog his contributions. Suffice it to say that he was one of many who didn’t wait for guidance from the Vatican before taking matters into his own hands. Indeed, at one point the Holy See cautioned Irish Church leaders not to involve themselves in secular affairs that were beyond the scope of their ministries (e.g., running soup kitchens, encouraging their parishioners to pressure the British for aid). Luckily, this guidance was ignored.

Take the case of Archdeacon O’Sullivan of Kenmare, County Kerry, who took it upon himself to import food directly, explaining to a Parliamentary commission that someone had to do it.

Or Paul Cullen, Rector of the Irish College in Rome (later Cardinal and successor to Daniel Murray as Archbishop of Dublin) who personally raised funds and ran interference between the Vatican and leaders of the Irish Church who felt that the Pope could have, and should have, done more.

Irish clerics reached out to their counterparts around the world, succeeding most significantly in raising money and awareness in the U.S. In fact, one of the first Irish aid committees (perhaps the first outside of Ireland) to be established was the Irish Charitable Relief Fund set up in December, 1845 by Father Thomas O’Flaherty, parish priest of St. Mary’s Church in Salem, Massachusetts. At the time, Father O’Flaherty raised the not insignificant sum of $2,000!

In short, the Irish Church stepped up to the plate at a time of national catastrophe while the Vatican’s efforts to aid Famine victims were limited at best. Then, again, the Famine was only one challenge in Pius’ 32 year tenure, one in which the dogma of the Immaculate Conception (accepted by rank and file Catholics for hundreds of years) was finally defined; and Papal Infallibility accepted. Clearly Pope John Paul II saw something in Pius IX to admire, for he was responsible for the veneration and beautification of the man – two of the 3 steps toward canonization.

* these public prayer sessions lasted three days (an indulgence of 7 years – a reduction, presumably, in Purgatory time – was granted to those attending) and the stated goal wasn’t just to help Irish Famine sufferers but to ask that famine not be visited on other parts of Europe. Now I believe in the power of prayer, but it must be coupled with human action to the extent within our power. I can not imagine a deity who would accept/demand less of us.